Project Summary

Along the North Shore of Lake Superior, residents and land managers have watched forests of paper birch and aspen decline over the past several years. Conifer regeneration that would be expected to replace the short-lived birch and aspen has been nearly absent, leaving many areas at risk of transitioning from forested cover to brush and grassland. Out of concern for the vitality of this coastal forest, the Superior National Forest developed the North Shore Forest Restoration Project.

Climate trends in northern Minnesota point to a future that will be warmer and more variable, presenting greater stress for boreal species such as paper birch, white spruce, and balsam fir. Early public feedback on the proposed North Shore Forest Restoration Project indicated that it should include a robust assessment of potential climate change impacts. Based on an explicit consideration of the potential effects of climate change on the project area, the project team made some important modifications to the proposed action to increase the resilience and adaptive capacity of the forests in the project area. These modifications range from identifying north-facing slopes and cold pockets where paper birch may fare better in the future, to restoring poor-quality birch stands with appropriate climate-adapted forest species such as white pine and northern red oak. This represents an early example in the Northwoods where planners were able to explicitly consider climate change effects during the NEPA process.

External Source

Related documents and resources

References

Handler, S.; Duveneck, M.; Iverson, L.; Peters, E.; Scheller, R.; Wythers, K.; Brandt, L.; Butler, P.; Janowiak, M.; Shannon, P.D.; Swanston, C.; Barrett, K.; Kolka, R.; McQuiston, C.; Palik, B.; Reich, P.; Turner, C.; White, M.; Adams, C.; D'Amato, A.; Hagell, S.; Johnson, P.; Johnson, R.; Larson, M.; Matthews, S.; Montgomery, R.; Olson, S.; Peters, M.; Prasad, A.; Rajala, J.; Daley, J.; Davenport, M.; Emery, M.; Fehringer, D.; Hoving, C.; Johnson, G.; Johnson, L.; Neitzel, D.; Rissman, A.; Rittenhouse, C.; Ziel, R. 2014. Minnesota forest ecosystem vulnerability assessment and synthesis: a report from the Northwoods Climate Change Response Framework. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-133. Newtown Square, PA; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 228 p.

Swanston, Chris; Janowiak, Maria, eds. 2012. Forest adaptation resources: Climate change tools and approaches for land managers. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-87. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station.121 p.

Superior National Forest Project Documents - North Shore Restoration Project

[block:views=slideshows-block_20]

Project background and scope

Prior to European settlement, the North Shore of Lake Superior was comprised of a healthy mixture of conifer-dominated forests. Logging in the late 1800s and early 1900s removed most of the white pine and white cedar, and the forest that grew back is heavily dominated by paper birch and quaking aspen.

Coastal forests provide many critical ecosystems services to coastal communities in the Great Lakes region, they help to stabilize stream banks and reduce erosion, increase infiltration, attenuate flooding, improve water quality, and provide habitat for culturally significant wildlife like wolves, bears, and moose. In addition, Minnesota’s coastal forests support a thriving recreation and tourism economy, and many outfitters, restaurants, and lodges cater to the tourists who frequent the area each year. Each year many tourists make the drive along Scenic Highway 61, which follows Lake Superior’s coast from Duluth to the Canadian border.

Both the tourists who make this trip and residents who live in the area year-round have noticed a striking change in the landscape in the last few decades. Current stands of birch and aspen have reached their typical age limits and nearly 80 % of the birch forest along the North Shore are old and dying. In addition, conifer regeneration is nearly absent in the understory of North Shore forests due to fewer older pine and cedar trees to provide seed, increased competition from native bluejoint grass, and heavy deer browse. Both the decline of aspen and birch and the apparent lack of conifer regeneration have prompted attention and concern from many agencies and landowners in the region.

Many stands of birch and aspen have reached their typical age limits and are old and dying, while conifer regeneration is nearly absent in the understory of North Shore forests. Credit: Superior National Forest

As a result, the Superior National Forest (SNF) like many other land managers in the area, is trying to restore forests in this landscape through active forest management. In 2013, SNF staff partnered with the State of Minnesota and the Grand Portage Tribe as well as a broader group of stakeholders called the North Shore Forest Collaborative (NSFC) to begin developing the North Shore Forest Restoration Project. All partners shared the primary concern of restoring white pine, white cedar, and other native plants to the area to ensure the health and resilience of the forest for which the area is renowned. For this specific project, SNF staff on the North Shore Interdisciplinary Team designed restoration treatments that would occur on SNF lands only.

The public had an opportunity to comment on the proposed North Shore Restoration Project during the 30-day scoping period required by NEPA. This feedback indicated that this project should include a robust assessment of potential climate change impacts. The SNF invited the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science (NIACS) to participate in a project planning meeting to help the team assess climate impacts on the goals of the project and design possible climate adaptation actions.

Recognizing that climate change will significantly alter the landscape as we see it today, the SNF North Shore project team considered information from a recent climate change vulnerability assessment for northern Minnesota forests. Northern Minnesota has experienced substantial changes in temperature and precipitation over the past 100 years, and the rate of change appears to be increasing (see details on climate trends: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/45939).

A few projected climate impacts that could be particularly important for the North Shore project area include:

- Temperatures in northern Minnesota are projected to increase across all seasons over the next century, with dramatic warming most likely in winter (2 to 12 °F).

- Precipitation is projected to increase in winter and spring across a range of climate scenarios, but there is greater uncertainty for summer precipitation – slight increases or large decreases are possible.

- Intense precipitation events are likely to continue to become more frequent.

- Snowfall is projected to continue to decline across the assessment area, with more winter precipitation falling as rain.

These climate trends point to a future that is warmer and more variable, presenting greater stress for boreal species such as paper birch, white spruce, and balsam fir. The steep terrain and shallow soils along the North Shore make the area more susceptible to flooding from heavy rain events, as was experienced in the summer of 2012.

Conversely, the southern aspect, warmer conditions, thin soils, and longer growing season could combine to make water stress more challenging for forests in this landscape. High deer populations mean that many preferred browse species (e.g. white pine, oak species) may have a hard time establishing without protection from herbivory.

Project Process and Implementation

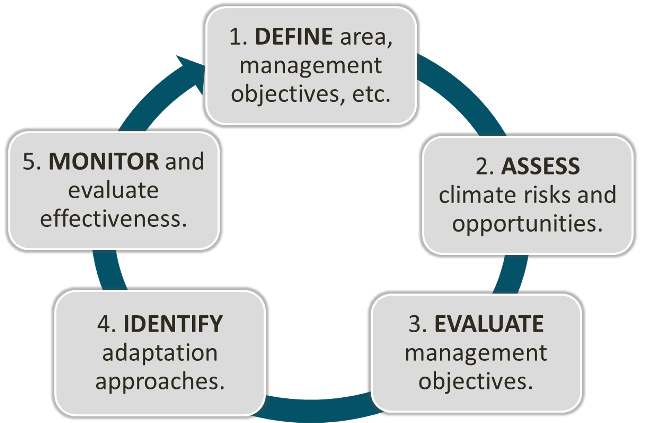

As a part of its Climate Change Response Framework, NIACS has developed a flexible process to help forest managers and landowners address climate change called Forest Adaptation Resources (FAR). This process includes an Adaptation Workbook, which asks forest managers to consider a series of questions to focus their thinking on potential climate impacts and adaptation actions for a particular project with real-world management goals.

During a 2-day workshop in April 2013, NIACS led a discussion among the SNF staff involved in planning the North Shore Forest Restoration Project. This team outlined the major goals of the project and considered how a range of broad-scale projected climate change scenarios might affect the particular landscape along the North Shore. NIACS shared information on general climate change trends and projections from the Minnesota Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment mentioned above, and resource specialists from the SNF (silviculture, soils, hydrology, wildlife, fire and fuels, etc.) used their own local knowledge and expertise to consider how the general projections might play out locally within the project area. Then the team thought critically about how climate change might present both challenges and opportunities for the management goals of the North Shore Forest Restoration Project, and brainstormed a wide range of adaptation tactics that could address expected climate impacts. A “menu” of adaptation actions from the FAR document helped the team generate specific ideas. Finally, the team discussed key monitoring items that would be helpful to determine if adaptation actions were effective.

A summary of the process from the Adaptation Workbook. The North Shore Restoration Project used this process to incorporate climate change into their plans.

Project Outcomes

The workshop mentioned above occurred shortly after the public 30-day scoping period for the project. After going through the Adaptation Workbook, SNF staff continued to think about possible adaptation actions and refine the North Shore Forest Restoration Project. Importantly, the team recognized that many of the management actions they already had planned also had benefits for climate change adaptation. Also, northeastern Minnesota may turn out to be one of the best possible “refuge” areas in the region for boreal species like paper birch and white spruce. Therefore, the team ultimately decided to proceed with many of the original goals and objectives of the project. Several modifications were added to the Proposed Action to increase diversity and future management flexibility, and some of these included:

- Identifying the best possible locations to retain paper birch on the landscape for the long-term, including stands of healthy paper birch, areas with north-facing slopes, and cold pockets.

- Identify stands of old, poor-quality paper birch for restoration to other appropriate native or climate-adapted forest types.

- Increasing the proportion of planted white pine, a species expected to fare better under climate change.

- Planting additional native species that are present in the surrounding landscape that were not originally part of the project design, including bur oak, and northern red oak.

- Try a variety of deer herbivory protection strategies – fences, tree cages, bud caps, and/or repellent sprays.

Adding these adjustments to the original Proposed Action will help the Superior National Forest restore forest cover along the North Shore, and accomplish the objectives of restoring native vegetation communities, improving wildlife habitat, improving watershed health, providing sustainable timber products and reducing hazardous fuels.

A final Decision Notice was issued for the North Shore Forest Restoration Project in August of 2014. More information about the final decision and planned actions is available on the Superior National Forest website. Implementation of the project will begin in 2014 and continue for the next several years.

Project challenges and lessons learned

After piloting the Adaptation Workbook process to consider climate change on the North Shore Forest Restoration Project, the Superior National Forest has continued to use this process for other NEPA projects. A few lessons learned and improvements include:

- Holding webinars with project team members prior to the in-person workshops. The purpose of these webinars is to review basic information on observed and projected climate change, as well as adaptation concepts. Covering this information ahead of time has helped make sure all team members are prepared for the discussion and it has streamlined the workshop process.

- In some cases, particularly where there is adequate information on climate change impacts, it may be most effective to consider climate change early in the NEPA process. The Superior NF has tended to use the Adaptation Workbook prior to scoping in subsequent projects.